The Frats Quintet were a vocal group popular in the 1950s in Jamaica who sang traditional folk music that is still performed today. Songs like “Linstead Market” “Sammy Dead-Oh” and “Slide Mongoose” (also titled “Sly Mongoose” at times or just “Mongoose”) are staples of the Jamaican culture. One of the very first recordings of these songs came from the Frats Quintet and Edward Seaga, who had been researching and recording folk traditions during this time, had his hand in helping to put these songs in people’s homes, or at least those who owned a record player.

Two years earlier, in 1956, Seaga had recorded and released his “Folk Music of Jamaica” recording with the Smithsonian. This came as a result of his study of revivalist cults including Pukkumina, Kumina, and Zion. He had been speaking to organizations in Jamaica upon his return from studying in the United States, having obtained a degree in anthropology from Harvard in 1952. Perhaps he was getting his feet wet for a political career, as he entered this arena in 1959 as the youngest member in history of the Legislative Council, appointed by Sir Alexander Bustamante (nick-namesake of Prince Buster). He then became elected to Parliament in 1962 for the West Kingston district and was appointed to the Cabinet as Minister of Development and Welfare where he championed Jamaican arts, music, and culture, especially in the name of tourism. Of course, he later went on to become fifth prime minister of Jamaica in the 1980s. I am writing a book this summer on Seaga’s role in the promotion of ska during the post-independence years, as well as all of the efforts during this time to establish Jamaican identity through ska.

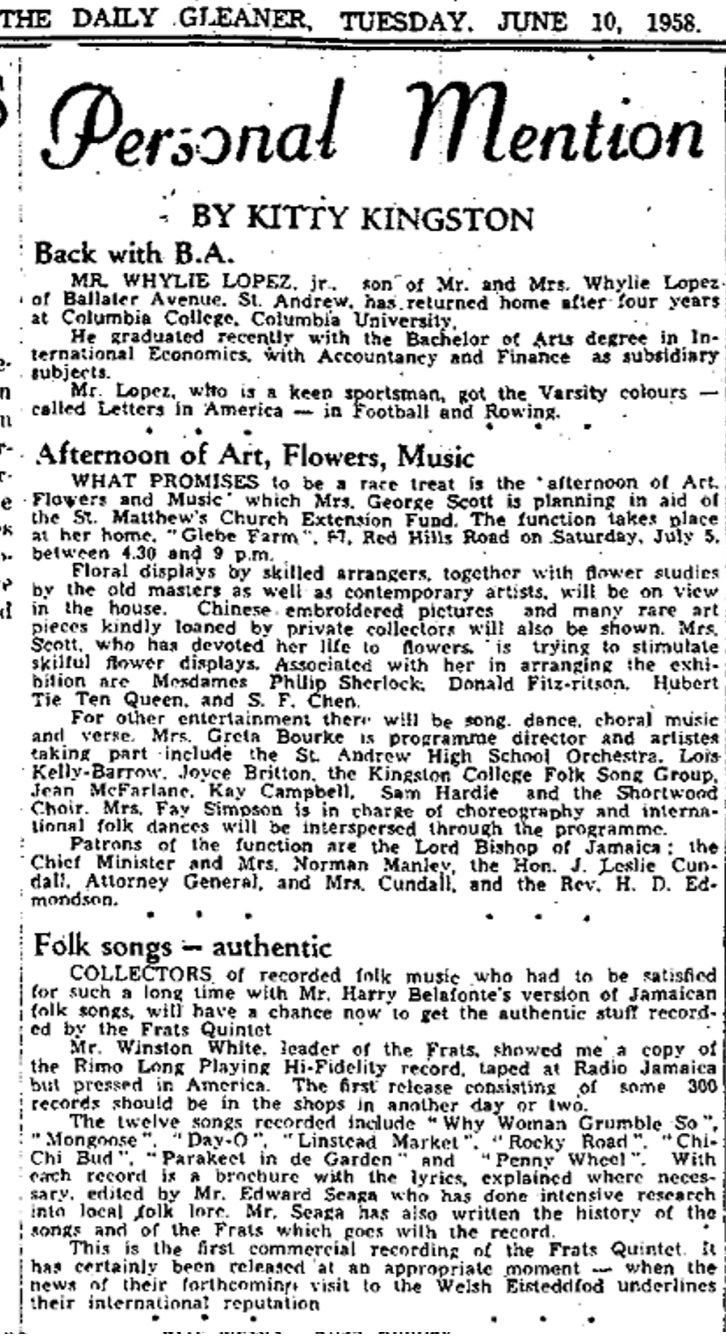

I came across this short article in the Jamaica Gleaner from June 10, 1958 that announces this Frats Quintet recording, which was recorded in Kingston, but pressed in the United States.

Here are a few photos of that actual album:

Remembering the Frats Quintet

Published: Wednesday | July 22, 2009

Members of the 1950s group Frats Quintet from left, Henry Richards, Winston White, Granville Lindo, Sydney Clarke and the only surviving member, Wilfred Warner (back). – Contributed The following is an article on 1950s Jamaican folk group Frats Quintet.

It was written by Patrick Warner, the son of one of the group’s members, and previously appeared in Canada’s Abeng News.

In the years before reggae, rocksteady and ska put Jamaica on the world musical map, mento and folk ruled the roost and the top folk exponents of the day were the Frats Quintet.

None of the Frats Quintet members were formally trained in voice dynamics. They sang for the love and appreciation of the art and a fondness for the songs, the majority of which originated from the plantations and from the hearts of the slaves who would sing as they worked. Since work time conversation was not allowed, music not only entertained and made work more tolerable, but messages were conveyed in song. Even post-Emancipation songs were composed and sung in the same manner to make heavy work light, while some songs reflected the social order of the day.

Before the Frats Quintet, there was the Young Men Fraternal. Their home base was the East Queen Street Baptist Church under the baton of J.J. Williams. Back in the day, it was the largest men’s choral group in Jamaica, and the sound they produced could make your hair stand on end or bring you to tears. A Sunday night evensong at the church was a treat not to be missed.

As a child, I can clearly remember visiting the Baptist Church a few times to hear the Young Men’s Fraternal sing to a packed house on a Sunday night. They would always be elegantly dressed in their vicuña cream jackets, white Oxford shirts, black bow ties and black trousers. The overflowing audience would take their places anywhere that offered a good vantage point; some were content to just listen.

It was from this group that the Frats Quintet was formed in 1951. The five, young men, Sydney Clarke, Henry Richards, Granville Lindo, Winston White and my father, Wilfred Warner, travelled the length and breadth of the island on a busy schedule, in addition to working their full-time jobs.

Household name

“Over the period of one year, we must have performed in every parish and major town in the island, as well as overseas,” muses my dad, the sole survivor of the group. “We rehearsed in the evenings after work, because our weekends were solidly booked at the hotels, and on Sunday, the services.” He never hesitates to add confidentially: “I met your mother at a performance in Savana-la-Mar you know.”

The group became a household name in Jamaica in the ’50s, doing ads on the radio (who could forget Ajax, the foaming cleanser?), and travelling the world, representing Jamaica on the international music scene. Some well-known songs from their repertoire included Linstead Market, the lament of the vendor as her provisions return unsold from the market, Shine-Eye Gal (she want, and she want, and she want everything!), Sammy Dead-Oh, and Nobody’s Business, which Peter Tosh retooled to the popular reggae beat.

I can remember once attending a night function at my elementary school where the quintet was to perform, and the police had to be called to restore order as a stampede occurred outside the school grounds. The concert was sold out, and spectators were positioned in trees just to hear Jamaican folk music. It was a night to remember.

There was always music in the home; I would be doing homework to the sound of folk music or negro spirituals from the rehearsals, and when those rehearsals were over, my father would exercise the double bass of his vocal chords loudly enough to wake the dead. Perhaps, with this immersion, there was absolutely no way I could avoid becoming a member of The Jamaica Folk Singers later on, but that was a different era.

The Frats Quintet also became the musical ensemble on and offstage for the National Dance Theatre Company, and their crisp trademark a cappella interspersed the scenes in a few of our pantomimes.

Most memorable recording

The quintet also ushered in Jamaica’s Independence celebrations, and sang their way into a few televisions around the island to welcome the now-defunct JBC TV. One of the group’s most memorable recordings, according to my dad, was providing the backup for late Soprano Joyce Laylor when they recorded the timeless Jamaican classic Evening Time, a celebration of the end of the workday, the setting sun and the cool evening breeze.

“You could feel the energy in the studio,” he beams, “and we were so in sync together, even the first take was exceptional.” My father is fond of reminding me that, in those days, there was no fooling around in the recording studio, as all artistes had to perform together on a single track. “It had to be perfect the first time,” he reflects.

The most disappointing moment for the group? Although the exact date is not clear in his mind – he remembers the late 60s – my father still has an angry glint in his eyes when he recalls jazz diva Nina Simone being booed onstage by an unappreciative audience at the Carib Theatre. Apparently, the quintet had warmed the stage for her, and when she appeared, the audience expected her to open with one of her more popular numbers. When she didn’t, they did not hesitate to voice their disappointment. Father still bristles, he says, with the shame.

The Frats Quintet took Jamaican folk songs on the international stage, performing at UN functions in New York, Expo ’67 in the Jamaican Pavilion and before world dignitaries in Montreal, the popular Eistedfod Music Festival in Wales (1958) where they copped a second-place award, and while in Britain gave a command performance for Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip.

Later, there was another performance on tap for Princess Alice, the then Chancellor for the University of the West Indies, and the group also performed on many occasions in Cuba, much to the delight of Fidel Castro. As Jamaica’s musical ambassadors, they performed for visiting dignitaries at state functions and dinners.

For my father, the ire of the Nina Simone episode is only eclipsed by the much-publicised disappearance of audio and video material from the JBC archives. “So much of our rich cultural history – gone just like that,” he snaps, full of emotion, and suddenly, the fire is gone from his eyes. At least in his head he still has the folk songs he can remember.

Enjoyed reading this blog. As a DJ of African Caribbean origin but not actually Jamaican, I’ve learned a a little about folk music out of interest. I enjoy listening to Mento, Calypso and folk songs. Thank you for helping to broaden my knowledge.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comments and support!

LikeLike

I will always remember this group of remarkable men. One of my uncles, Mr Popsey Jackson. sang with them from time to time as a filling in for a member who could not make the trip. When they came to Bath in St Thomas to perform, it was usually without advanced notice. The word would go out that they were in town and crowds would appear as if out of thin air. These were some of the most memorable times of my childhood in Bath and truth be told, it is they who first sparked my interest in music and performance.

LikeLike

Beautiful! Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike